The Troubles in Northern Ireland have an enduring iconography, even twenty-five years on from the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. This is partially to do with the long tradition of attaching social, political, and historical narratives to place that has been well-observed in the island of Ireland. Especially in the working-class areas of Belfast and (London)derry, one cannot go anywhere without coming across an area of significance to the Troubles (Feldman 436-437). As a result, specific neighborhoods and buildings have acquired a certain status in the public consciousness of the Troubles. One of the most notorious of these is Divis Flats, designed and built on the lower Falls Road in Belfast between 1966 and 1972 (Page 3). The flats would eventually consist of 12 interconnected eight story deck access blocks as well as one twenty-story tower, and had about 2,400 residents in 850 flats (Roy 1).

From the beginning, the flats were controversial, as part of a slum clearance project by the Northern Ireland government. The Pound Loney, the neighborhood torn down to make way for the flats, was known as a safe and close-knit community, with family and friends living close to each other, and many small pubs and shops. However, the Victorian-era housing often lacked amenities such as central heating or running water (Roy 19). Thus, when the Divis Flats housing project was announced, the reaction amongst the residents of the Pound Loney was decidedly mixed, with many choosing to accept a move to Divis in order to stay close to family and friends, despite their reservations about the buildings. This attitude can be seen in a quote from a man who had lived in the Pound Loney before moving to Divis Flats– “the Pound Loney is where I was born and where I will die even if the Brits change the name to Divis Flats; for Christ sake, they might as well have called it Long Kesh” (Dowler 102). The flats themselves were described as “Europe’s youngest slum” even before construction had been completed (Page 3).

The flats quickly gained a reputation for violence, with a British Army base built on the roof of Divis Tower in 1972. This observation post was used for surveillance of the flats themselves, as well as the greater Lower Falls Road (Page 13-14). Soldiers lived on the top two floors of Divis Tower, and supplies were transported by helicopter (Alfaro & Roulston 28). The military made use of the design of the flats to carry out regular searches of the inhabitants (Roy 33). Resistance among the population, and the high rates of membership of first, the IRA and PIRA, and later, the INLA, meant that it became colloquially known as the “planet of the Irps,” a slang term for the INLA’s associated political party, the IRSP (Roy 8-9). Death and injury due to paramilitary or military activity were relatively commonplace, including among children as young as nine or ten (Alfaro & Roulston 28; Roy 9).

In addition, there were several issues with the facilities of the flats, such as damp, mold, lack of laundry facilities, broken elevators, dirty stairwells, broken lights, overflowing rubbish chutes, the inability to supervise children, not enough play areas for the over-a-thousand children, broken railings, inability to stay warm, and more (Alfaro & Roulston 28-29; Roy 30-31, 33). Anger over living conditions led the residents to campaign for the demolition of the flats, which finally occurred in the summer of 1993, with only the tower (and the army base on top) remaining (Dowler 103; Roy 13-14). The army base itself stayed until 2005 (Page 21). Despite the fact that the flats are long-gone, they have endured as a symbol of the Troubles in the public consciousness, and still regularly feature in UK and Northern Ireland press relating to disappearances and murders from the time period.

Citations:

Dowler, Lorraine. “Preserving the Peace and Maintaining Order: Deconstructing the Legal Landscape of Public Housing in West Belfast, Northern Ireland.” Urban Geography, vol. 22, no. 2, 2001, pp. 100–105, https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.22.2.100.

Feldman, Allen. “Violence and Vision: The Prosthetics and Aesthetics of Terror.” States of Violence, edited by Fernando Coronil and Julie Skurski, The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2006, pp. 425–459.

Gómez Alfaro, Garikoitz, and Fearghus Roulston. “Nostalgia for ‘HMP Divis’ and ‘HMP Rossville’: Memories of the Everyday in Northern Ireland’s High-Rise Flats.” Journal of War & Culture Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, 2021, pp. 25–44, https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2021.1873532.

Page, Adam (2017) Appropriating architecture: violence, surveillance and anxiety in Belfast’s Divis Flats. Candide – Journal for Architectural Knowledge (10). pp. 90-112. ISSN 1869-6465

Roy, Megan Deirdre. “Divis Flats: The Social and Political Implications of a Modern Housing Project in Belfast, Northern Ireland, 1968-1998.” The Iowa Historical Review, vol. 1, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1–44, https://doi.org/10.17077/2373-1842.1001.

Object 1: “High Life” part 1 BBC One documentary, 2010

The story of Divis Flats continues to attract attention today. This is a TV documentary from BBC One Northern Ireland first aired in 2010. As well as providing a general history and overview of the flats, it also contains several interviews of various players in the story of the flats. One of those interviewed is the architect, Frank Robertson. Interestingly, he shies away from really acknowledging issues with the design itself, instead blaming the residents of Divis Flats for issues with the facilities.

However, one of the most interesting aspects of this documentary is what it doesn’t acknowledge, namely the bias present in the planning of the flats. Similarly to the Bronx in New York City, the Pound Loney community was razed so that a highway could be built– in this case, the M1 motorway (Roy 4). In addition, by concentrating the Catholic community in high-rises, unionist politicians were able to ensure that Protestants would continue living in the nearby areas of the Shankill Road and Sandy Row, instead of moving further out and leaving room for Catholics to dominate the constituencies in the inner city (Roy 39). This process of ghettoization “implemented imperial and colonial agendas” by reducing social contact between opposing sides (Feldman 433-434). The British Army also had a hand in planning public housing in Belfast, which can clearly be seen in the design of the flats, where every door pointed towards the army post (Roy 24).

This documentary makes no reference to any of the above, perhaps unsurprisingly, as the BBC is the national broadcaster of the UK, and is thus predisposed to slant its news coverage towards the British state. Divis Flats is instead presented almost paternalistically, blaming the poor conditions on the residents just not knowing how to live in a modern high rise.

Object 2: The British Army base on Divis Tower in the early 2000s

“A man does not have a chance in these streets in the sky. At least in the old Pound Loney if you saw them coming to lift you, you had a chance to make a break for it down the street.”

–a resident of Divis Flats, as quoted in Dowler 102

Many of the residents of Divis Flats described it as a prison, with it even earning the nickname “HM Divis” (Alfaro & Roulston 28). This was not least due to the presence of the British Army base on top of Divis Tower, and the constant surveillance, humiliation, and harassment that entailed. Although the majority of people in Divis were initially not opposed to the British Army, this quickly changed due to a series of riots in which the military shot several people, including small children (Roy 26). The resulting widespread hostility amongst the residents led the army, in turn, to regard all residents of the flats as potential IRA members, which made them even more hostile, in a vicious cycle of violence.

The British Army took to conducting house searches, which the residents referred to as raids (Page 10). They blocked off entrances and exits by positioning soldiers on the stairs and lifts, and detained the people they rounded up in the laundry tower (Page 10-11). They also changed the flats to fit their needs, breaking and blacking out lights so that they would be harder to see, and cutting the cables on all of the lifts after the murder of two soldiers by an IRA bomb hidden in the lift shaft (Alfaro & Roulston 33-34; Roy 33).

The army frequently pasted photos of residents taken from the surveillance post onto the windows of flats below, heightening the paranoia of the residents (Page 14). This also served as a tool of humiliation, with one man interviewed telling a story of a friend of his who adjusted his zipper after he realized it was undone, and was featured on posters the next day with the caption “Do you want your children around this man?” (Dowler 100).

Object 3: “Ulster’s Lost Generation” New York Times article by John Conroy, 2 August 1981

Divis Flats attracted attention from outside of Northern Ireland due to its status as a symbol of the Troubles and a republican stronghold. This is a New York Times article from 1981, about three months after the death of Bobby Sands. It discusses the high crime rate in Divis Flats, its perception among the community, and the everyday violence, as well as the role of the IRA in policing Divis Flats. Among the people interviewed are a Divis resident in his twenties who is not part of the IRA, the press officer for Sinn Fein, and a representative of the RUC.

One of the main focuses of the article is the prominence of kneecapping as a form of punishment used by the IRA in their policing of their community. One man interviewed in the article, who was accused of car theft, was offered the choice of either cleaning the walkways of Divis Flats or being kneecapped by the IRA, and chose the kneecapping, because he felt that cleaning walkways would be too humiliating.

Another aspect of Divis Flats touched on by the article is its perception in the wider community of Belfast. Although the Divis resident interviewed looked for a job as an auto mechanic, as soon as he said that he was from the flats, he was turned down. This was not unusual; when applying for jobs, residents of the flats would often list the address of a friend or relative because of Divis’s notoriety (Roy 25). Partially because of this, the unemployment rate in the Falls area tended around 68 percent, and 51 percent of Divis residents depended solely on welfare (Roy 2).

Object 4: Photo of children playing outside Divis Flats by Chris Steele-Perkins, 1978

This picture shows children playing outside of Divis Flats, with the remnants of the former Pound Loney community behind them. Children in the flats were usually unsupervised, as the design of the flats did not allow parents to easily observe their children (Roy 40). This meant that they were targets, both as potential recruits for paramilitaries, and for being injured by the paramilitaries or the army. The first child killed in the Troubles was nine-year-old Patrick Rooney, who was killed in Divis Tower in August of 1969 when the RUC fired a machine gun into the flats (Alfaro & Roulston 28). In a study comparing the children from Divis Flats to those from a nearby terraced Catholic housing estate, children from Divis Flats “were shown to have significantly higher rates of emotional distress.” (Roy 20)

The poor conditions of the flats themselves also created danger for children. In a 1987 health and housing survey, 36 percent of the children in the flats had frequent coughs and 10 percent had asthma symptoms caused by the ever-present damp and mold, and in the mid-1980s, a child died by falling through a broken railing on the stairway (Roy 33-34). However, there were still moments of fun for the children, with one former resident recalling:

“I remember one of the things we used to do if we were bored was to walk round the balconies looking for black bows on the doors and go in to see the corpse. It didn’t matter if you knew them or not […] God love some of those poor people, we must of had them tortured, cos if it was a good corpse we’d go back a couple of times.”

– Veronica, quoted in Alfaro & Roulston 38

Object 5: “Riots in the Divis Flats” by Peter Marlow, 1981

Given the status of Divis Flats as a republican stronghold, riots and protests were not uncommon. This photo depicts rioters after the death of Bobby Sands, the first of the hunger strikers in the Maze prison to die. During the hunger strikes, young people living in the flats “hijacked and burned over 100 cars, buses, and trucks around the complex, barricaded all of the entrances, and turned Divis into a “no go” area,” sheets were draped over balconies to block surveillance from the tower, and armed IRA and INLA members patrolled openly (Roy 29). The security forces were not able to get into the flats for six weeks.

This is only one of many examples of resistance against the security forces. When soldiers tried to carry out raids, women would rattle pot lids off of the balconies to alert the surrounding area, and children would throw trash (Alfaro & Roulston 35). In 1983, over 50 percent of residents actively supported either the IRA or the INLA (Roy 38). These paramilitaries set booby traps in the flats for the soldiers, including a pipe bomb in a stairwell in February of 1974 that injured eleven residents, but not the patrol unit it was intended for, and fired on soldiers in Divis Tower (Roy 8, 11).

There were also more peaceful forms of protest, such as a 1971 rent strike in protest of internment that saw 100 percent participation from the residents of the flats (Dowler 103). In addition, many Divis residents attended rallies of the Women’s Peace Movement, a peaceful protest group, in 1976 (Roy 10).

Object 6: “Belfast’s Divis Flats to be demolished” Guardian article by Bob Rodwell, 9 July 1986

Loading…

Loading…

Although residents had been calling for Divis Flats to be demolished since 1973, only a year after its completion, the Housing Executive did not accede to their demands until 1986 (Alfaro & Roulston 29). This article from the Guardian announcing the upcoming demolition cites vandalism and safety concerns for the military and police as reasons for razing the flats. This may have been the government’s stated reasoning, but for the residents, this was the culmination of over a decade of sustained protest, both through raising public awareness and forcibly rendering apartments uninhabitable.

The Divis Residents’ Association was formed in the late 1970s or early 1980s, and aimed to “raise public awareness through publications and studies” (Roy 12). They listed violence, social problems, and structural defects as reasons for demolition, but their biggest one was the “feeling of hopelessness, of being trapped in Divis” (Page 18). The Divis Demolition Committee, meanwhile, formed in 1979, decided to take matters into their own hands. They would make recently vacated flats uninhabitable by taking windows and doors out of the frames, breaking the frames, knocking through walls, pulling out electrical fittings, and closing the flats up with cinder blocks (Page 19-20; Roy 12). They also released rats in the office of the Housing Executive to show what daily life was like in Divis (Page 19). Sean Stitt, a member of the Committee at the time, explained their actions by saying “We can say to the Housing Executive, that if they don’t demolish Divis, the people of Divis Flats will certainly demolish it” (qtd. Page 20).

Ultimately, though all of the reasons given above may have played a role in Divis’s demolition, the major one was the same reason the Pound Loney had been torn down thirty years before: to make way for the M1 motorway (Roy 12-13).

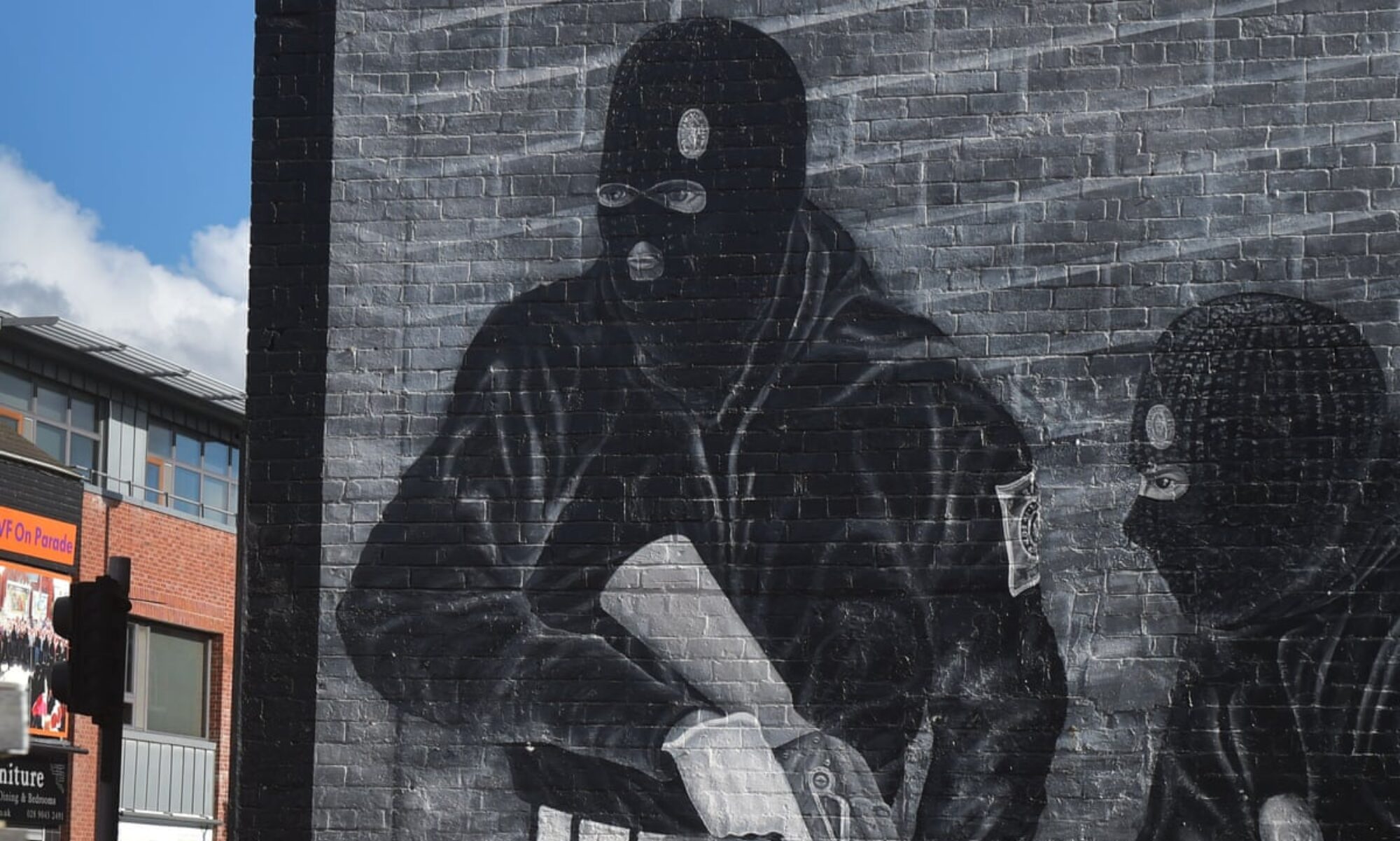

Object 7: Photo of mural calling for demilitarization of Divis Tower by Peter Moloney, 19 February 2003

The flats themselves were completely demolished by the summer of 1993, but the tower remains to this day. The military base on the tower continued to keep watch over the lower Falls Road area until 2005, meaning that the residents there continued to feel a sense of paranoia from being observed almost twenty years after the announcement of the demolition of Divis Flats (Roy 2). This photograph, taken in 2003, shows a mural asking for the removal of the Divis Tower army base with the tower itself looming in the background. The mural was located on the International Wall on Divis Street, and was one of the first things a visitor to West Belfast coming in from the city center would see. Although the rest of Belfast is shown as a group of much shorter buildings silhouetted against the sky in the background, Divis Tower is large and bright, showing that it doesn’t belong.

Symbolically, the military base on Divis Tower was a remnant from the violent past for those living near it. It “became metonymic with the conflict itself, especially in its urban manifestation” (Alfaro & Roulston 35). While the blocks of flats became part of the fabric of a sort of mythos of republicanism during the Troubles, the Tower itself is not gone and is thus harder in some ways to reconcile with the violence that occurred there. Today, the Tower houses older people who need public housing, and is considered desirable enough that there is a long waiting list to live there.

Object 8: Photo of Jean McConville with three of her ten children, Associated Press

Though Divis Flats has (other than the tower) physically faded into the past, it is very much still alive in the public memory. This is a photo of Jean McConville, who was “disappeared” and murdered by the IRA on suspicion of being an informant in 1972, shown here with three of her ten children. She lived in Divis Flats when she vanished, and remains one of an extensive list of crimes from the Troubles that endure in public memory. She is particularly notable because of Gerry Adams’s alleged association with her disappearance and murder (Alfaro & Roulston 28). This particular case threatens the political status quo in Northern Ireland, making it clear that the violent past lurks just below the surface.

The flats’ symbolic status is furthered by the fact that their existence maps pretty closely onto the timeline of the Troubles. The first block was opened in May of 1968, four years before Bloody Sunday, and the final block was demolished in 1993, five years before the Good Friday Agreement was signed (Alfaro & Roulston 27). High and low points in the intensity of the conflict were directly echoed in Divis Flats. For this reason, it is often perceived and portrayed as a microcosm of the Troubles– the conflict centered in one area. This can be seen in movies about the Troubles. For example, the 2014 film ‘71 features Divis Flats as a nightmarish symbol for Northern Ireland as a whole (Alfaro & Roulston 36). Ultimately, perhaps a single area that experiences so much concentrated death and violence can never truly be erased from the public memory, even long after the physical structures are gone.

Bibliography:

British Army. “Soldiers Work at the Top of the 19-Storey Divis Tower.” BBC News UK, BBC, Belfast, Northern Ireland, 2005.

Conroy, John. “Ulster’s Lost Generation.” New York Times, 2 Aug. 1981, pp. 17–21.

Cunningham, Gemma, and Paul McGuigan. High Life Part 1. BBC One– High Life, Episode One, BBC One Northern Ireland, 2010, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00v9kl0. Accessed 2023.

Dowler, Lorraine. “Preserving the Peace and Maintaining Order: Deconstructing the Legal Landscape of Public Housing in West Belfast, Northern Ireland.” Urban Geography, vol. 22, no. 2, 2001, pp. 100–105, https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.22.2.100.

Feldman, Allen. “Violence and Vision: The Prosthetics and Aesthetics of Terror.” States of Violence, edited by Fernando Coronil and Julie Skurski, The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2006, pp. 425–459.

Gómez Alfaro, Garikoitz, and Fearghus Roulston. “Nostalgia for ‘HMP Divis’ and ‘HMP Rossville’: Memories of the Everyday in Northern Ireland’s High-Rise Flats.” Journal of War & Culture Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, 2021, pp. 25–44, https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2021.1873532.

“Jean McConville with Three of Her Children.” RTÉ Ireland, RTÉ Ireland, Belfast, 2015.

Marlow, Peter. Riots in the Divis Flats. New York City, 1981, https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AMAGNUMIG_10311502840. Accessed 2023.

Moloney, Peter. “Demilitarise Divis Tower.” Peter Moloney Collection, Extramural Activity, Belfast, 2013, https://petermoloneycollection.com/2003/02/19/demilitarise-divis-tower/. Accessed 2023.

Morrison, Brian. “Divis Flats.” Troubles Archive, Arts Council of Northern Ireland, 2014, http://www.troublesarchive.com/index.php/artforms/architecture/piece/divis-flats. Accessed 2023.

Page, Adam (2017) Appropriating architecture: violence, surveillance and anxiety in Belfast’s Divis Flats. Candide – Journal for Architectural Knowledge (10). pp. 90-112. ISSN 1869-6465

Rodwell, Bob. “Belfast’s Divis Flats to Be Demolished.” The Guardian, 9 July 1986. Nexis Uni, https://advance.lexis.com/document/?pdmfid=1516831&crid=f8a0684a-051b-4614-acf1-3ac5de0a39ff&pddocfullpath=%2fshared%2fdocument%2fnews%2furn%3acontentItem%3a40GH-JC70-00VY-82XJ-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=138620&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=-znyk&earg=sr0&prid=7527a2a9-3358-433b-bed8-1cbdd8a2e23e&aci=la&cbc=0&lnsi=62415cbb-4e27-48e7-928d-8af07d9e3e43&rmflag=0&sit=null. Accessed 2023.

Roy, Megan Deirdre. “Divis Flats: The Social and Political Implications of a Modern Housing Project in Belfast, Northern Ireland, 1968-1998.” The Iowa Historical Review, vol. 1, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1–44, https://doi.org/10.17077/2373-1842.1001.

Steele-Perkins, Chris. Outside Divis Flats. New York City, 1978, https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AMAGNUMIG_10311511498. Accessed 2023.