Summary

This post examines the role the peace walls have played in the organization and daily lives of those who live closest to them. Exploring the history behind the walls and different attitudes and opinions surrounding them, it is clear that the walls have created an atmosphere of division past even traditional sectarian divides.

A Brief Overview of the Peace Walls in Belfast

Peace Walls in Belfast, Northern Ireland have been part of the architectural landscape of the city since the beginning of the Troubles. The first was put up in 1969 and over the next 30 years, nearly 30 miles of walls could be erected through the city. During this time existing walls would also be added with a variety of materials. These walls were designed to be a temporary structure that would come down in a manner of months or a few years (Leonard and McKnight 2011). They were not. In the time since their erection, the peace walls have gone on to become major cultural markers in Northern Ireland, both for the region as a whole and for the communities they divide. They act as monuments to and reminders of the sectarian division within Belfast and Northern Ireland more broadly (Ravenscroft 2009). In doing so, rather than keeping the peace, they have provoked fear by limiting contact between the two major communities and by increasing the securitization of the political problems in Belfast.

Their role in the fabric of Belfast’s culture and political discourse cannot be understated. During the Troubles, around 70% of those killed in Belfast were killed within half a kilometer of a peace wall (Leonard and McKnight 2011). After the signing of the Good Friday agreement in 1998 the walls have come to represent the lack of progress within the region and the continued need for changes within the structures of government (Gormley-Heenan and Byrne 2012). The peace walls act as sites for artistic expression, urban decay, political protest, and in some limited cases reconciliation. Their centrality to the politics of Northern Ireland is a result of where they sit geographically. They act as the interface between majority Catholic communities and majority protestant communities and were primarily designed to limit cross-community interaction.

Contact theory hypothesizes that limited interaction between various ethnic and political groups is one potential reason for outgroup animosity. Therefore, increasing levels of contact between these varying groups through both intentional and passive contact might reduce such tensions in a divided society. The Peace Walls have done the opposite (Dixon et al. 2020). Rather than foster connections between communities, they have reinforced physically located tribes. In doing so, the walls have shaped public opinion about the other community and limited the ability to create a fully integrated society.

The peace walls have also contributed to the securitization of political issues in Northern Ireland. In many ways, they become part of the story of “the chicken and the egg.” The walls were installed to protect citizens from violence. However, in their installation, they also promoted specific ways of behaving by merely existing. In this sense, the walls are both a product of the division within the city as well as a self-reinforcing mechanism that continues the sectarian divide.

Developing a plan to remove the peace walls has been a long-standing goal of the Northern Irish Executive. Their targeted date to remove them all was 2023. It seems this plan will not come to fruition as currently, there are more peace walls active in Belfast than there were 25 years ago (Alcaraz 2023). This is the result of mixed public sentiments about the peace walls and where Northern Irish society as a whole will be going in the next few years.

In Belfast, the peace walls represent both an interesting and strange study of several aspects of peace and conflict. They have acted simultaneously as a physical barrier to violence but also as an abstract barrier to peace; promoting the separation rather than integration of the communities that surround them.

What they Look Like. What they Represent.

The image above provides a view of what a peace wall looks like. It is neither pretty nor is it inviting. In fact, it is meant to have the exact opposite effect. Designed to separate each other, they became more and more brutish as the years went on. When deemed not to have their job well enough, the government would add more walls on top of what already existed, generally becoming closer and closer to bare fencing.

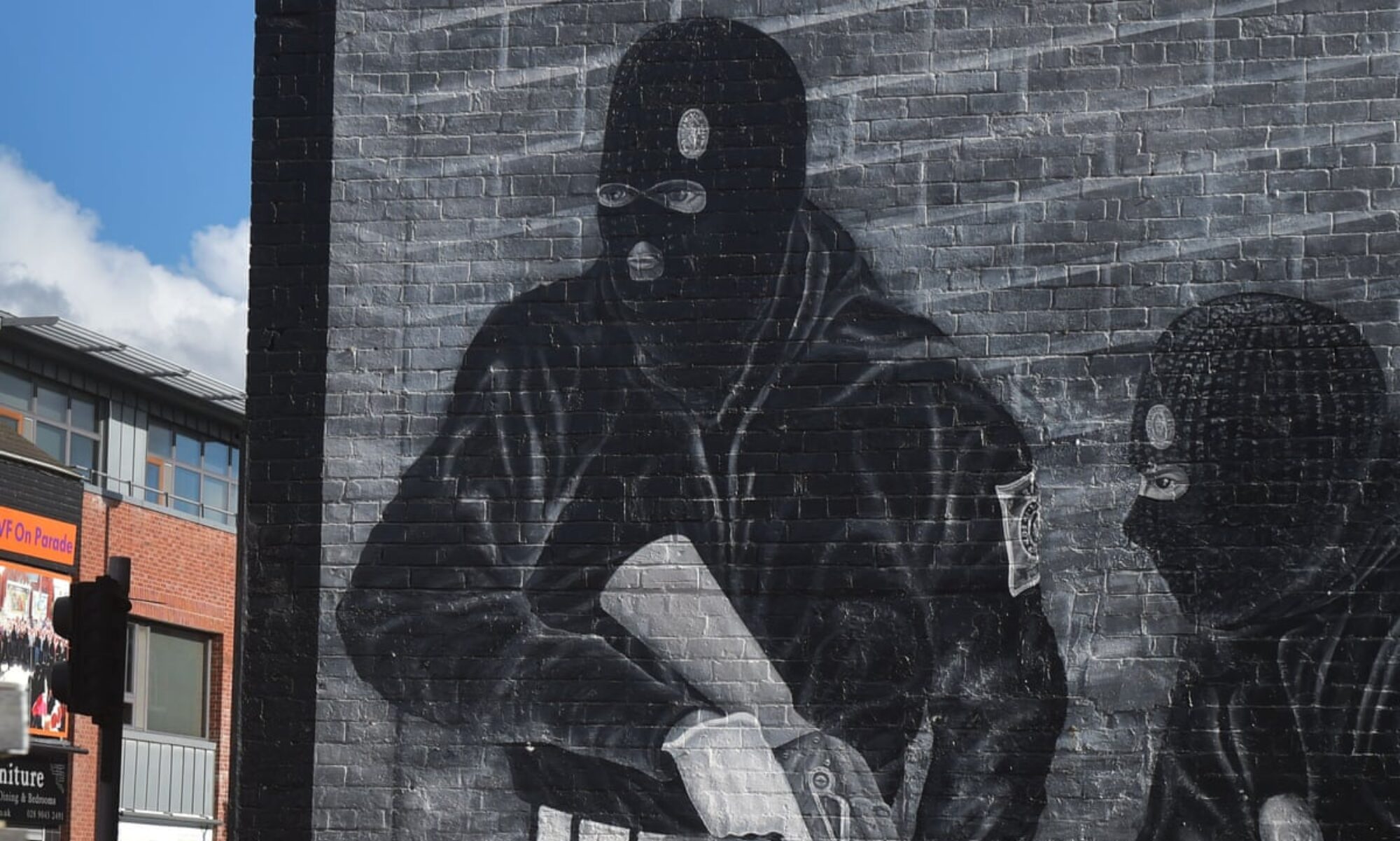

In some instances, like this one, the walls extend upwards of 30 feet (Leonard and McKnight 2011). These walls would extend through backyards, streets, and parks all the while looking like something from a prison, dividing the inside from the outside. In addition to creating a clear and ominous divide between the two communities, they were also spaces that created intra-community solidarity (Ravenscroft 2009). One way this was accomplished was by utilizing them as sites for prominent murals. The Murals one would see on a daily basis would be dependent on which side of the wall they lived on. All of them in support of their own community. In the most concrete sense they say “On this side of the wall, we are family. On that side of the wall, they are the enemy. With this, the peace walls represent both a stark physical barrier between the two communities in Belfast as well as a strong rhetorical argument in favor of communal tribalism.

The Stories Told.

Reflected Lives is an interview-based Oral History done to collect attitudes and stories about the communities that the Peace Walls surround. Specifically, community members from Short Strand and Inner East were interviewed. In several chapters, the report documents how walls and the Troubles more broadly changed society and oftentimes made life difficult. Interviews occurred with those who both experienced life in Belfast before the walls were put up and young adults who were only a few years old when the Good Friday Agreement was signed.

What becomes clear in reading through the report is that the walls were not just physical. Prior to many of the peace walls going up in the 70s, rapid changes in the community dynamic occurred. What were once mixed streets soon had families selling their homes and moving towards more homogeneous neighborhoods Due to the start of the troubles, the walls were first psychological, and then physical.

Once the walls went up that division solidified. It changed the daily lives of those living in the community. The walls normalized the division of “us from them” and therefore also normalized the violence that came along with them. It was now expected that people would riot at the walls, and even try to launch things over the top of them. Both communities now had a target for their violence and their anger.

Because many who now live in these communities have not lived a life without the walls, and those that did were still children, much uncertainty exists about their removal. Some express the opinion that they want them gone, but worry that the community will descend into even more violence without them. Others are more pessimistic and want to see the walls heightened even further.

Economic Suffering Around the Peace Walls.

These two maps show an overview of where the peace walls exist in the context of Belfast as a city. The map on the left shows the specific geographical locations of the walls and the breakdown of the religious affiliation of the neighborhoods in Belfast. The map on the right details socio-economic deprivation based on seven different factors, with darker red marking a more deprived area compared to the rest of Northern Ireland.

In combination, these two maps highlight how not only do peace walls exist at the interface between communities with large majorities of their own faith but they also mainly exist in the top half of the most deprived communities within Northern Ireland (NIMDM17- Results 2017). Lower socio-economic status can lead to feelings of being left behind. This can materialize in an increased likelihood to join more militant or extremist groups (Smith 2018). Therefore, the lack of socio-economic opportunities for people within the communities that the peace walls divide might in part explain why they have been flashpoints of violence.

The presence of the peace walls can further contribute to this economic deprivation. They limit trade and commerce between neighboring communities. They can also limit external investment due to negative perceptions of the communities around the walls being “unsafe.” These negative perceptions only exacerbate social inequality seen around the walls.

The Economic Incentives the Walls Provide.

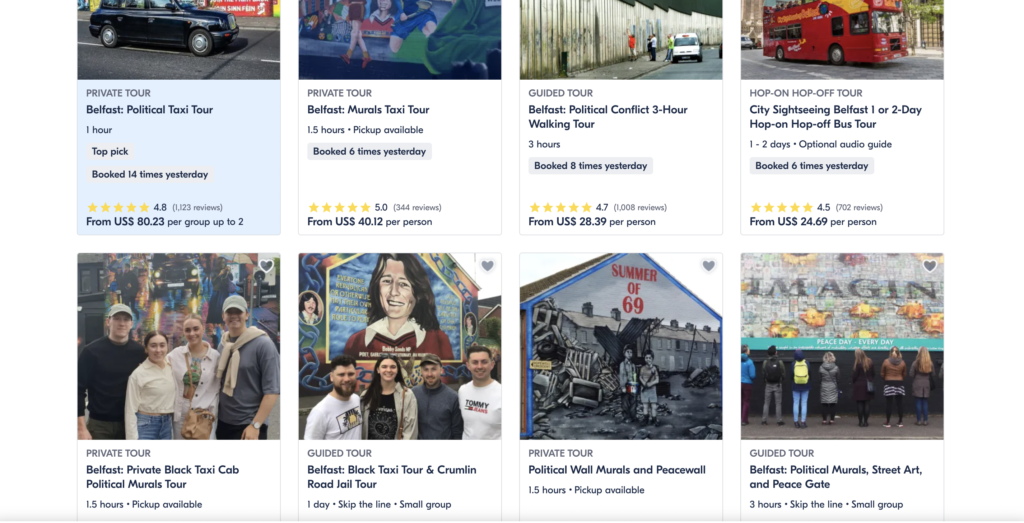

Post troubles Northern Ireland has been punctuated by a period of increased economic activity, especially tourism. The above image is a screenshot of different private tours that a tourist can go on throughout Belfast. While not explicitly just about the Peace Walls most of these tours have some focus on the Peace Walls during the trip.

The commodification of the peace walls can create perverse incentives for citizens and communities they border, and of the city more broadly, to support their removal. Because they encourage economic activity and growth, the walls provide an avenue to bring money to the communities they surround. As these communities are historically and currently underserved this revenue may be vital sources of income for some community members. Deconstructing the walls would limit this source of income and thus leave some in the communities worse off.

So while it might be to the benefit of the broader Northern Irish community to take down the walls, the walls themselves have created an economic landscape that leads some to push for their continued existence (Brunn et al. 2010). Likewise, these tours can force the past into the present, leading those involved in economic activity surrounding the walls to relive the troubles. Again, making sectarian identities and history more salient than in a world without walls.

Youth, History, and Nothing to Do.

This clip discusses the role of the peace walls in the way young adults behave and act. Interviews with community leaders trying to reintegrate the areas around the walls discuss trends that they see in the younger generations who live near the walls. They Discuss how rioting and protesting have been ingrained in community culture for decades. As such when young adults are bored and do not have anything to keep them occupied, such as during the summer, they turn to throwing things over the walls or making petrol bombs.

While not explicitly addressed in the clip, there is also an economic component to this behavior when idle. As noted above, the communities surrounding the walls are of lower socio-economic status. Therefore, parents are likely to be less engaged in their child’s life. Families simply don’t have the money to send their children to day camps, sports camps, or be home when they are to keep them occupied.

In an interview with one young adult, identifies family life as one of the main causes of out-group animosity, “it’s just the way I’ve been brought up.” This is why even for younger generations the divisions the peace walls create are so hard to shake. As a child in one community, you hear stories about the violence and the wrongs that have been done to your brothers and sisters and because of the walls, you probably have never had more than a passing conversation with someone from the other community. Therefore there are no counterpoints to the stories and stereotypes you grow up listening to. The peace walls and the insular communities they create necessitate the transfer of biased intergenerational knowledge.

The Interface: a Poem about the Walls.

The Peace Walls in Belfast have split public sentiment on what they represent and how to best solve continued conflict in the city. Through writings, poems, art, and conversation citizens have taken to artistic forms of expression to explain their points of view. Taking a markedly negative view of the peace walls, this Piece entitled “The Interface: Peace Walls, Belfast, Northern Ireland” by James O’Leary centralizes one of many opinions surrounding them. It should be noted that general popular sentiment is much more mixed, with many believing that the peace walls are still necessary to this day (Gormley-Heenan and Byrne 2012).

The piece discusses the emotion, the oddity, and the fear that the peace walls elicit. It highlights how intrusive and controlling they are. Even more, this poem discusses how much of a cultural staple the peace walls are. It describes the murals that adorn them and how they have been institutionalized in law and regulation. Referring to the peace walls as interfaces, the piece alludes to the walls being a primary point of contact, or lack of contact, between the Catholic and Protestant communities. The use of the word “interface” also elicits a sense of friction between the two communities. The walls, therefore, become a point of tension, heat, and anxiety within Northern Irish society.

While generally negative, there are glimmers of hope within the author’s views. He presents a picture of the peace walls being “ a discussion regarding the optimal conditions for contact” (O’Leary 2017, 143). Because for as much harm as they have done to the material and cultural landscape of Belfast, changing the scope of the walls, or their removal entirely, is one potential avenue that contact can easily be increased and society can continue its healing.

Contemporary Security Issues at the Walls.

This news clip produced by BBC interviews several different families who live next to, or very close to the peace walls in 2021. In the video, they discuss their thoughts and opinions about the peace walls and generally express anxiety about the security situation surrounding the walls.

The clip was produced in response to major protests that occurred along the walls, which highlights how the walls are still major sites for protests and marches to this day. Overall, opinions about the peace walls are mixed. On the one hand, their support for them has declined over time, and on the other, those closest to them still believe they are important in keeping the peace (Dixon et al. 2020). They have become so ingrained in the history and culture of communities that nearly 25 years on from the Good Friday Agreement that most of the walls throughout Belfast are still up.

With rising tensions in Northern Ireland surrounding Brexit and the lack of a functioning regional government, protests may become more frequent. If this is the case, then peace walls will act as a primary point of tension in the city as they have in the past.

Because the walls act as physical demarcations of sectarian identity, protesting around them brings salience to a conflict that is now in its fifth decade. The walls have therefore acted as another point of gathering for protest in addition to the traditional city centers that usually draw large crowds of protesters. Thus contributing to the lack of normalized of politics in Northern Ireland.

Removing Barriers and Healing the Divide.

The Belfast Interface Project is a civil society group within Belfast aiming to build cross-community understanding and facilitate dialogue in the communities around the peace walls. They operate in a constellation of other similar organizations throughout Northern Ireland aiming to increase contact between the Catholic community and the Protestant community.

Their work aims to bridge the divide between communities that the peace walls divide. Creating a shared narrative of why the walls went up, what they have done to community, and what a possible future without the walls all are important aspects of this process. One of the projects they undertook to help do so was the Reflected Lives Oral History seen above. This along with other creative projects might be one main avenue to healing the divisions the peace walls enforce.

The Interface Project makes clear that the continued presence of the walls is a symptom of broader and more systemic community distrust. Likewise, the mere existence of their organization represents how sticky the attitudes and issues are around the peace walls. Work needs to continuously be done to build bridges between interface communities. Through concerted efforts of those both in and outside of the community, progress can be made.

Works Consulted.

O’Leary, James. 2017. “The Interface: Peace Walls, Belfast, Northern Ireland.” Footprint Delft Architecture Theory Journal (19): 137–44.

Alcaraz, Teresa García. 2023. “Belfast Has More Peace Walls Now than 25 Years Ago – Removing Them Will Be a Complex Challenge.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/belfast-has-more-peace-walls-now-than-25-years-ago-removing-them-will-be-a-complex-challenge-203975 (May 29, 2023).

BBC News NI. 2021. “Cages around Houses: Life at Belfast’s Peace Wall.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vcD4mG7YO_8 (May 31, 2023).

Belfast Interface Project. 2018. “Reflected Lives Intergenerational Oral Histories of Belfast’s Peace Wall Communities.” https://www.belfastinterfaceproject.org/sites/default/files/publications/ReflectedLives-Publication-for-web_25april2018.pdf (May 30, 2023).

Brunn, Stanley D., Sarah Byrne, Louise McNamara, and Annette Egan. 2010. “Belfast Landscapes: From Religious Schism to Conflict Tourism.” Focus on Geography 53(3): 81–91.

Dixon, John et al. 2020. “‘When the Walls Come Tumbling down’: The Role of Intergroup Proximity, Threat, and Contact in Shaping Attitudes towards the Removal of Northern Ireland’s Peace Walls.” British Journal of Social Psychology 59(4): 922–44.

Gormley-Heenan, Cathy, and Jonny Byrne. 2012. “The Problem with Northern Ireland’s Peace Walls.” Political Insight 3(3): 4–7.

Leonard, Madeleine, and Martina McKnight. 2011. “Bringing down the Walls: Young People’s Perspectives on Peace‐walls in Belfast.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 31(9/10): 569–82.

“NIMDM17- Results.” 2017. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. https://www.nisra.gov.uk/publications/nimdm17-results (May 30, 2023).

NorthumberlandPoster. 2021. “Belfast: Ward-Level Deprivation.” Reddit. https://external-preview.redd.it/4OGWq8MeQkqjtGqt3cLlBoGbddi17zVe1rO5Ru7khQM.png?auto=webp&v=enabled&s=fc61ead2e49f5995a55bbb0bf5570cf71925c465 (May 29, 2023).

“Peace Walls, Belfast – Book Tickets & Tours.” GetYourGuide. https://www.getyourguide.com/peace-walls-l11441/?cq_src=google_ads&cq_cmp=6654173973&cq_con=76427540862&cq_term=&cq_med=&cq_plac=&cq_net=g&cq_pos=&cq_plt=gp&campaign_id=6654173973&adgroup_id=76427540862&target_id=dsa-84666501466&loc_physical_ms=9019509&match_type=&ad_id=616359129300&keyword=&ad_position=&feed_item_id=&placement=&device=c&partner_id=CD951&gclid=Cj0KCQjw98ujBhCgARIsAD7QeAh8EHhqKF63ecBFNyibLXKpdKEtkRXFrMeLNM2jkoqn52oEHezrQt0aAjgCEALw_wcB (May 29, 2023).

“Peaceline Wall.” Troubles Archive. http://www.troublesarchive.com/artforms/architecture/piece/peaceline-wall (May 29, 2023).

Pulitzer Center. 2009. “In Focus Northern Ireland: In the Shadow of the Walls.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PkjqS-GtiT4 (May 31, 2023).

Ravenscroft, Emily. 2009. “The Meaning of the Peacelines of Belfast.” Peace Review 21(2): 213–21.

Smith, Allison. 2018. “Risk Factors and Indicators Associated With Radicalization to Terrorism in the United States: What Research Sponsored by the National Institute of Justice Tells Us Whitepaper.” U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.“Vision, Mission, Aims & Values.” Belfast Interface Project. https://www.belfastinterfaceproject.org/vision-mission-aims-values (May 31, 2023).