Michael Ge

The funerals of IRA volunteers would serve as an intersection of the Troubles. Various different people and organizations would come into contact with one another at this event. Over the course of the Troubles, the IRA lost many of its members due to deaths in combat against the state security forces, in prison, and in other incidents. The IRA would take care to honor its members who were killed in the line of duty. The IRA was a military organization with a strong and clear political focus. As such, it would ensure that its funerals would be conducted in a military style manner while also making sure to make a political statement by emphasizing the cause for which the IRA volunteer died for, a united Ireland. Thus, the funerals of IRA volunteers would attract considerable attention and allow the mourning of the fallen volunteer as well as sending a clear political message.

The deaths of republican paramilitaries would constitute a relatively small number of the total deaths during the Troubles (Sutton n.d.). Even though that is the case, many of their funerals would draw a significant amount of public attention and press coverage (Mulcahy 1995).

The funerals would often draw many spectators from the community where the funeral was being conducted as well as the neighborhoods that the funeral procession would pass through (Mulcahy 1995). There would also be Sinn Féin making an appearance and speech at these funerals, which is no surprise given the links between the political party and the IRA. The IRA would use these very public funerals to show their presence and honor its dead. The sacrifice of their volunteers would be able to be used to maintain their legitimacy as the organization leading the struggle for Irish unity (Sweeney 1993). The fallen volunteers would be remembered and honored at these funerals regardless of whether others in Northern Ireland would consider them to be terrorists and murderers. These public remembrances of IRA volunteers show a specific part of the human loss that was all too common during the Troubles and serve as a way of expressing republican identity.

Some of those being honored had taken lives and yet they were being honored. Their victims did not receive anywhere near as much coverage and attention as the funerals of IRA volunteers (Mulcahy 1995). This juxtaposition drew controversy from members of both communities in Northern Ireland. These funerals would gradually evolve from the Troubles to the present as the conflict winded down and some practices regarding funerals would have to change. The variety of ways the IRA was able to honor its members shows both its adaptability and consistency which it also demonstrated throughout its campaign against the British security forces.

Ultimately, the funerals of IRA volunteers would serve as a poignant reminder of the lives lost during the Troubles and remind all those observing the funerals, whether they agreed with the IRA or not, of what the volunteer believed in, fought for, and ultimately died for.

Artifact 1: The Funeral of Bobby Sands

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/ZNBHK7HXHX27SLGSUPHFYTGKSE.jpg)

Irish Times/Getty Images

This picture was taken at the funeral of Bobby Sands. Bobby Sands’ coffin is flanked by IRA volunteers as it is carried by the pallbearers. Sands’ family follows closely behind his coffin.

Bobby Sands, a well known IRA volunteer, had died on hunger strike as a protest against the policies of the British government. Sands’ actions received significant international attention, spreading awareness of the republican cause (McKeown 2021).

Looking at the picture, the funeral of Sands appears to have welcomed a large number of onlookers of all ages. Indeed, the funeral of Sands attracted thousands to mourn and watch in Belfast (Mulcahy 1995). The presence of the IRA would mean that its appearance would be at the very least tolerated by the family of Sands. Even with the presence of the IRA, Sands’ mother, Rosaleen, called for peace at the funeral (Downie Jr and Washington Post Foreigh Service 1981).

At the funeral, the IRA would conduct a volley salute and escort the coffin of Sands. Gerry Adams would also make an appearance at the funeral and he paid tribute to Sands (Downie Jr and Washington Post Foreigh Service 1981).

The funeral of Sands and this picture in particular represents the many complex and intertwining factors at play at the funeral of an IRA volunteer. There is the military and political aspect which would feature the volley salutes of the IRA and the tributes from Sinn Féin. Then there is the family of Sands and their wishes regarding the violence faced by the people of Northern Ireland. Finally, there is the public who have come to commemorate the life of Bobby Sands. The funeral would show the high degree of community support enjoyed by Sands (Mulcahy 1995). This support would allow for a political message that had the added bonus of legitimacy to be sent. All of these factors combined would allow for an effective political message to be sent with the funeral.

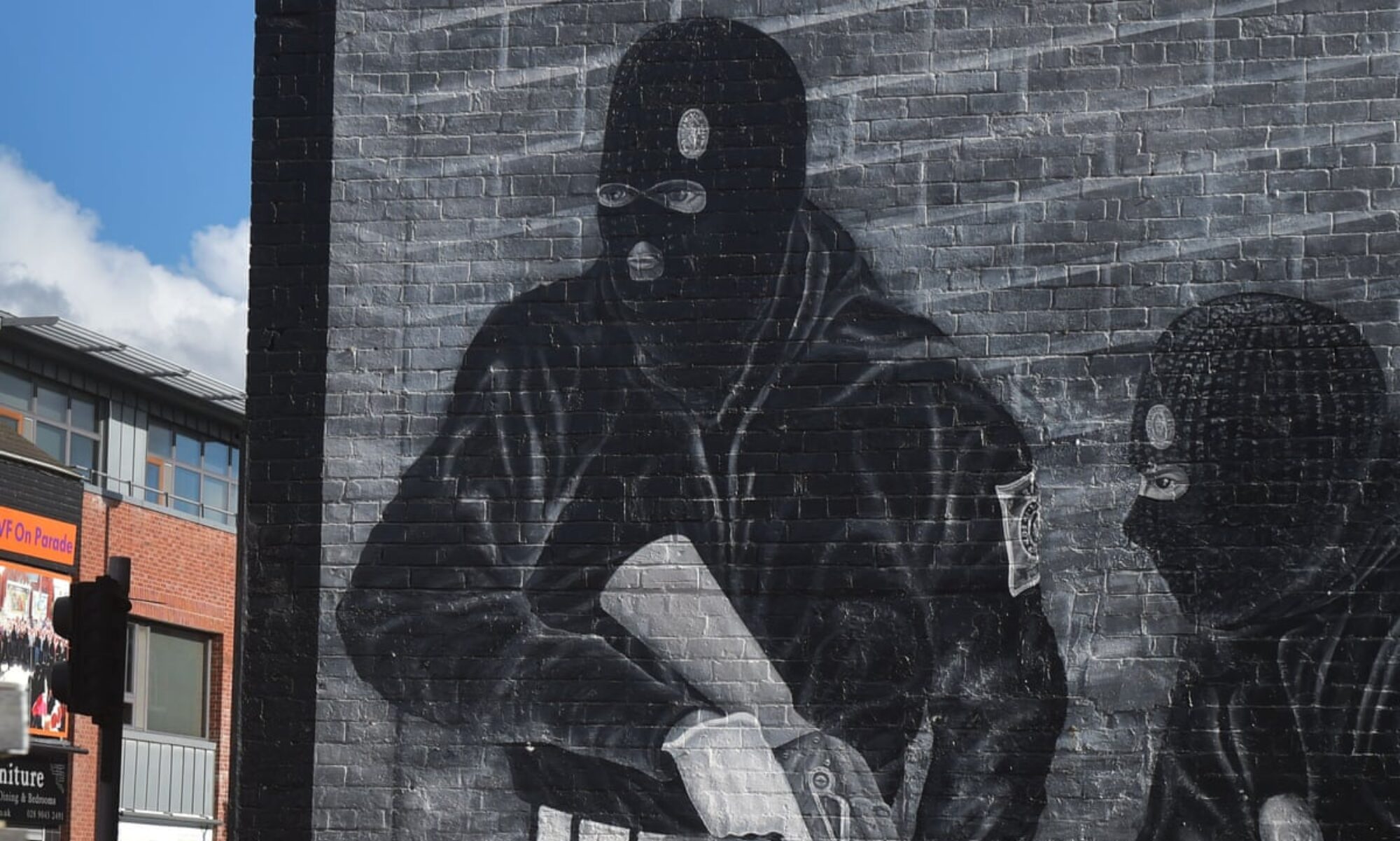

Artifact 2: The Three Volley Salute

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/AMSIBU4FM4UEPG7LFBOT3CUTDA.jpg)

Derek Speirs

This picture was taken at the funeral of hunger striker Joe McDonnell (Hanna 2016). At McDonnell’s funeral, there are three IRA volunteers front and center in military uniform and with their rifles raised. Surrounding them is a crowd of mourners and onlookers who have come to pay their respects to McDonnell.

In accordance with a military style funeral, there will be a three volley salute conducted. This form of salute would involve three soldiers each raising their weapons and firing three shots in unison, such an action would traditionally symbolize the continuation of fighting (Welch 2022). In this picture the three IRA volunteers performing this action.

The other eye-catching part of this picture is the Irish tricolor laid on McDonnell’s coffin. When combined with the presence of the IRA, there would be a strong message of Irish republicanism on display. The message would be clear for all to see, McDonnell had died for Ireland and the IRA would continue what McDonnell had fought for.

Despite its portrayal of itself as an army, its members still choose to hide their faces with masks and sunglasses. The IRA is aware that despite claiming to be an actual army, they would still have to hide their identities like how a fugitive would. Certainly the IRA would recognize that they were still fighting an insurgency as a paramilitary group and not as the military of a sovereign state.

The clear and elaborate way in which the IRA took to honor its dead shows how much it would value the sacrifices of its members. The military style funeral of an IRA volunteer is both one of commemoration and serves a large political purpose.

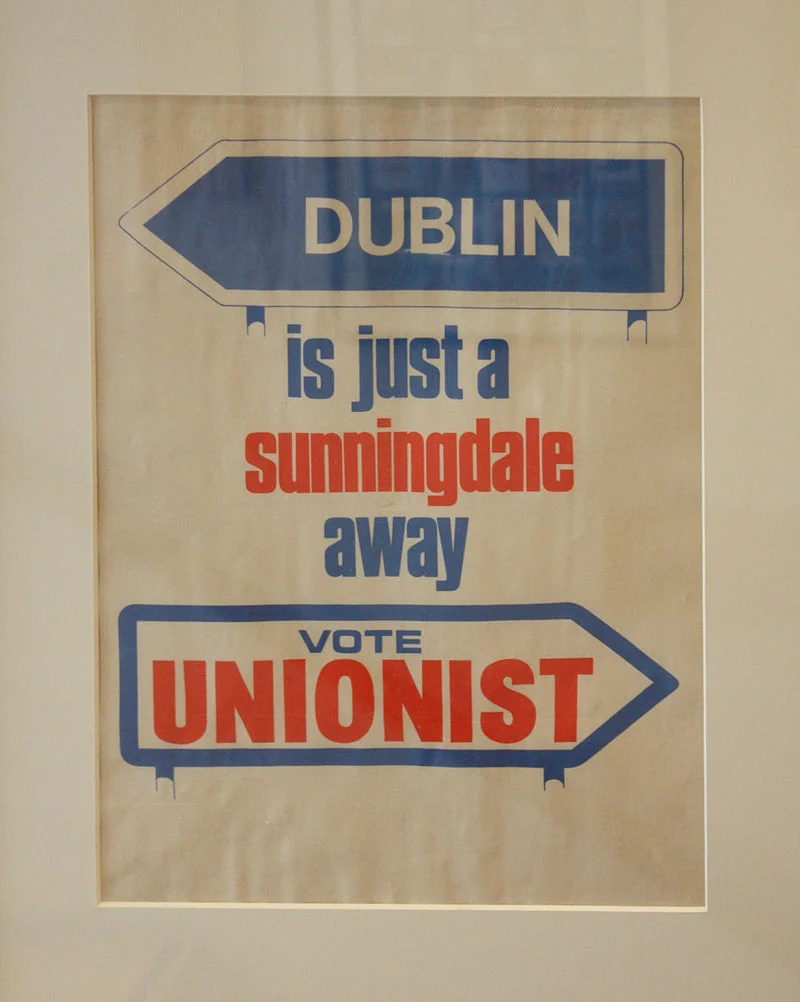

Artifact 3: The Unionist Response to the Funeral of Bobby Sands

It would be important to address how the unionist community of Northern Ireland would respond to the funeral of IRA volunteers. The unionist community constitutes a significant part of Northern Ireland’s population and it would be important to note how they reacted to the funeral of Bobby Sands. The high profile funeral of Bobby Sands was met with a strong reply and condemnation of the life and death of Bobby Sands from the unionist community.

This gathering was held in the center of Belfast and around two thousand people attended it. The gathering was held at the same time as the funeral of Bobby Sands and served to commemorate those who were killed by the IRA. Civilians made up most of the deaths that occurred during the Troubles (Sutton n.d.). Furthermore, the gathering served as a condemnation as what they would perceive as the glorification of the IRA and paramilitary violence.

The Union Jack is laid over the table next to Ian Paisley as he delivers a speech, sending a very explicit message of where they stood politically. Paisley’s speech can sum up the prevailing attitudes commonly associated with the Unionist community towards the IRA. Paisley condemned Sands as a terrorist and argued that the death of Sands was a suicide rather than a sacrifice. Bobby Sands would have a choice in choosing whether or not to live or die but the victims of the IRA did not have that choice is the feeling which sums up the attitude held by the unionists.

It is important to remember the highly polarized environment in which these funerals were held. The funeral of IRA volunteers would be no exception. The controversy which surrounded the funerals of IRA volunteers should be remembered. One side would view the funerals as honoring the fallen while the other would see it as glorifying the actions and lives of terrorists.

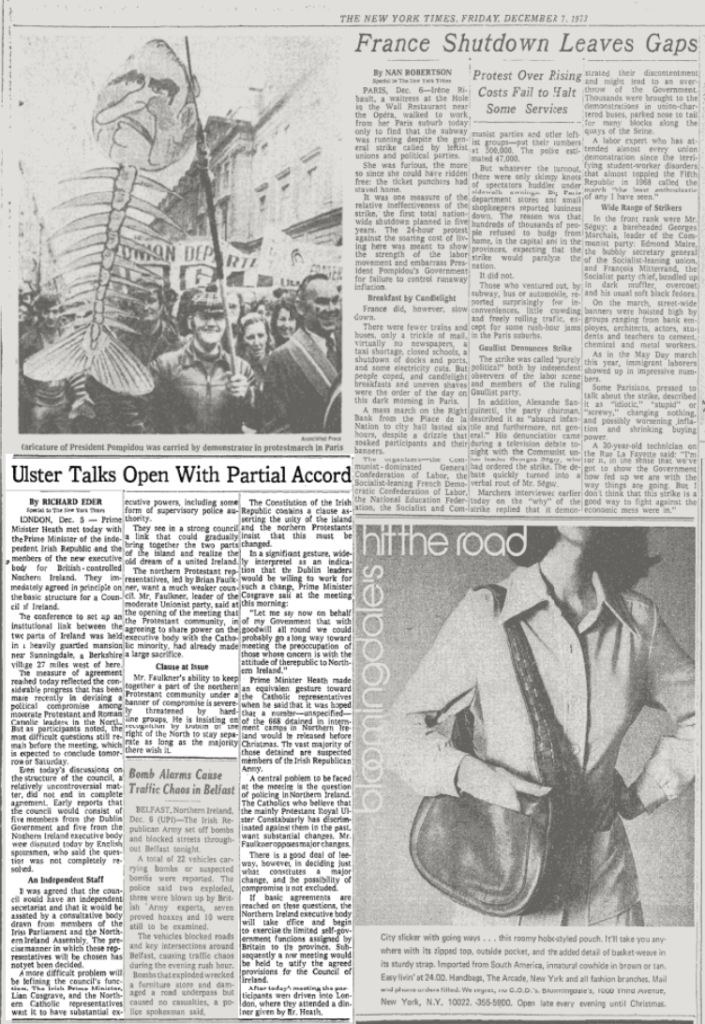

Artifact 4: The International Response

The deaths of IRA volunteers could often lead to a great deal of attention both on the island of Ireland and across the world. Oftentimes, the international response to these events would be much more sympathetic towards the nationalist cause. It is important to remember that the international condemnation of the British government was considerable (McKeown 2021). The IRA would be able to use the funerals for their political advantage by harnessing sympathetic coverage towards their movement.

This article from the Irish Press, a newspaper with its circulation based primarily in the Republic of Ireland. Here, the death of Bobby Sands received front page coverage from the newspaper. A collection of various responses from individuals and organizations were printed. The paper included a message from Taoiseach Charles Haughey who urged for peace and dialogue in the region. From the United States came a statement made by Senator Edward Kennedy which criticized the British government for allowing Sands to die.

What is most interesting from the front page is the statement from the IRA. The statement urged its members to have discipline while condemning the . The IRA would assert its authority over the death of Sands and make sure that any response would be by its order and not from any form of impulsive attack.

Importantly, the press coverage of the funerals would allow for the martyrdom of the IRA fighters to happen. And allowed for the IRA to maintain its legitimacy and authority as the face of the republican struggle. The IRA would also use these events to help drum up international support. With the funeral of Bobby Sands, Sinn Féin’s demands for no rioting were followed as they wanted the international media who arrived to cover the funeral to not be distracted by other events (Mulcahy 1995).

Artifact 5: Law Enforcement at Funerals

At the funerals of some IRA members, the state security services would try to actively thwart the IRA from paying tribute to its fallen members. This was the case at the funerals of IRA volunteers Edward McShaffrey and Patrick Deery. The RUC’s justification for their actions would be that they would be against the funerals becoming a display for paramilitary activities.

The RUC came out in large numbers and riot gear as they walked next to the crowd as they walked to a church. Afterwards, the RUC and the mourners would come into conflict and clash with one another. The clashes would initially be resolved and the cortege would continue towards the cemetery. When the cortege was moving towards the cemetery, a masked individual, presumably a member of the IRA, would fire off a volley near the two coffins. At first, the crowd would duck but they then broke out in applause once they realized what was happening. The RUC fired off plastic bullets at the mourners who responded with stones. Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams would also be at the funeral and later condemned the RUC’s actions (Northern Ireland Conflict Videos 2022b).

The funerals of McShaffrey and Deery show a defiance against the might of the state security services. The goal of the RUC to prevent a paramilitary display was thoroughly thwarted.

The ability of the IRA and Sinn Féin to maintain their presence at the funerals of IRA members shows their tenacity even in situations where rendering a funeral with a clearer IRA presence was impossible. Even at funerals there would still be conflicts and violence. The funerals acted as a continuation of that violence.

Artifact 6: Public Criticism of IRA Funerals

Frame of Video from RTE Archives

https://www.rte.ie/archives/collections/news/21267090-ban-on-ira-funerals-lifted/

The manner in which the funerals of IRA members were conducted would draw scrutiny and condemnation from both members of the public and officials. Specifically, the firing of bullets into the air by IRA members when they were conducting a salute over the coffin of a fallen IRA Volunteer led to a ban on IRA funerals being conducted in 1987. The argument made by the clergy in implementing the ban would be that the usage of firearms should not be allowed on church grounds as they would be inappropriate for funerals. The presence of firearms and salutes using them would also be avoided by the IRA on certain occasions. A scuffle between the crowd of mourners and the RUC at the funeral of an IRA Volunteer meant that the IRA chose to avoid conducting the salute out of concerns toward the safety of the funeral attendees. The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Tom King would argue that the funerals would have to be conducted lawfully and in a dignified manner. The definition of what would be considered dignified by the Northern Ireland Secretary would be much different from that of the IRA. Ultimately, the ban on IRA funerals was lifted by church authorities in 1988 (RTE 1988a).

The hastily conducted volley shows that it is much more disorganized than the elaborately conducted funeral of the hunger striker Joe McDonnell. The circumstances of the volley also showed the ability of the IRA to adapt to the situation at hand.

The condemnation that came towards the conducting of IRA funerals shows the scorn toward the IRA from many members of the community. It is important to remember that despite the large number of mourners at an IRA funeral, there would still be resentment and disdain towards the IRA. The views toward those who died and their activities did not draw universal support even from their own communities.

Artifact 7: Descents into Violence

Frame of Video from RTE Archives

https://www.rte.ie/archives/collections/news/21272007-soldiers-killed-at-ira-funeral/

IRA funerals were subject to violence during the Troubles. At Milltown Cemetery, an attack by a loyalist gunman would kill three and injure dozens more (Beiner 2007). One of the killed would be Kevin Brady, a member of the IRA. At the funeral of Kevin Brady, the mourners would descend upon two off-duty British soldiers, Derek Wood and David Howes, who were conducting surveillance duty at the funeral.

This video gives a clear view of the ensuing reaction of the mourners. The emotionally charged atmosphere of the funeral meant that when the two soldiers were discovered, the response was one of fury. Their car chaotically reverses as an enraged crowd surrounds it. The car tries to accelerate away, but its path is blocked by a car that maneuvers right in front of them. A furious crowd then surrounds the car preventing any means of escape. The next scene shows an individual in a light blue jacket breaking the passenger side window and kicking at the car door and the crowd then proceeds to surround the vehicle.

The actual killing of the two soldiers is not shown in the recorded footage. Later on, two bodies covered by blankets are shown following a police response.

This event shows how charged the atmosphere would be during the Troubles even at funerals. Even more so, the presence of or even hint of British security forces was not tolerated. The violence of the Troubles would continue even during times of mourning.

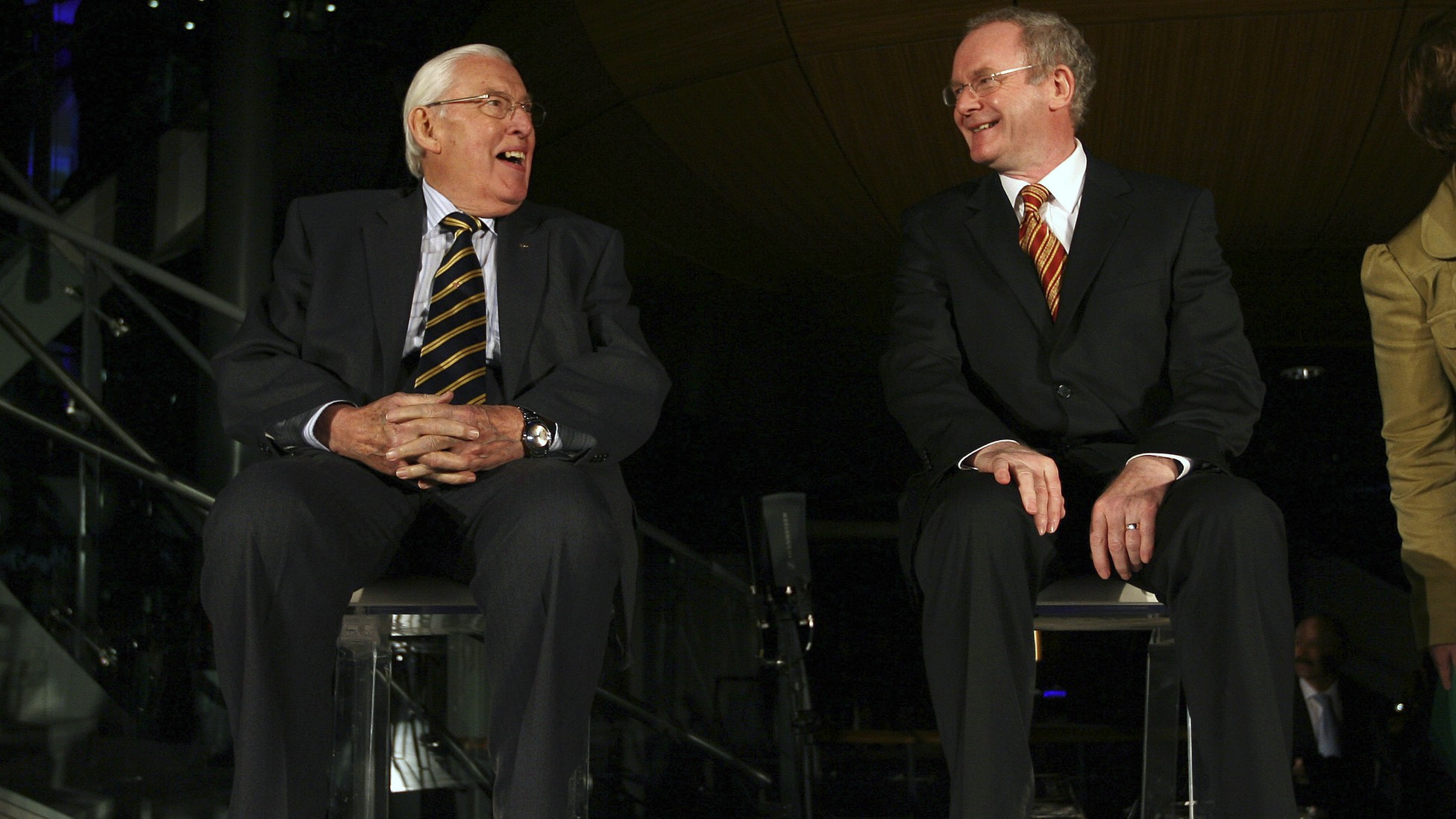

Artifact 8: Modern IRA Funerals

After the Good Friday Agreement, the IRA would decommission their weapons and end their military campaign (The Belfast Agreement 1998). This would mean that funerals would now have to be conducted differently from the way they were during the Troubles. This would mean that the previous way of conducting funerals for IRA members would have to change.

This video shows the funeral of Rita O’Hare, a member of Sinn Féin and the IRA. O’Hare would be arrested in Northern Ireland for attempted murder but ended up fleeing to the Republic of Ireland, and she would also serve three years in an Irish prison for explosives charges (Irish Times 2023). Afterwards, O’Hare would serve in a variety of high profile positions in Sinn Féin including as general secretary and represented the party in the United States.

The leader of Sinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald, deputy leader Michelle O’Neill, and former leader Gerry Adams were all present at O’Hare’s funeral and served as pallbearers. Adams would deliver the eulogy for O’Hare as well. In the eulogy, Adams made O’Hare’s paramilitary activities no secret and proudly stated that she was a member of the IRA.

The funeral shows a more civilian feel to it than previous funerals, showing the end of the Troubles and the long road to peace. The Irish tricolor is still present, but the lack of a paramilitary presence is the most telling. Even though there is a lack of paramilitary symbolism, Gerry Adams did not hesitate to name O’Hare’s paramilitary activities as something that should be honored by her grandchildren. So, even while Sinn Féin peacefully pursues its goals through the political process, they do not forget to honor their past members even if their way of honoring former members of the IRA has changed.

Works Cited

Ban On IRA Funerals Lifted. 1988a. RTE. https://www.rte.ie/archives/collections/news/21267090-ban-on-ira-funerals-lifted/ (May 31, 2023).

Beiner, Guy. 2007. “Between Trauma and Triumphalism: The Easter Rising, the Somme, and the Crux of Deep Memory in Modern Ireland.” The journal of British studies 46(2): 366–89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/510892.

“Bobby Sands Died 35 Years Ago Today: How The Irish Times Covered the News.” 2016. Irish times. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/bobby-sands-died-35-years-ago-today-how-the-irish-times-covered-the-news-1.2636487 (May 31, 2023).

Downie, Leonard, Jr, and Washington Post Foreigh Service. 1981. “Thousands Mourn at Sands’ Funeral.” Washingtonpost.com. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1981/05/08/thousands-mourn-at-sands-funeral/b3d0f22e-9693-404e-a9a8-5cdba17557db/ (May 31, 2023).

“Funeral of Rita O’Hare.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3uPgU3M3gp4 (May 31, 2023).

Hanna, Erika. 2016. “Photographing the Hunger Strikes.” Irish times. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/photographing-the-hunger-strikes-1.2552410 (May 31, 2023).

McKeown, Laurence. 2021. Time Shadows: A Prison Memoir. UK: Beyond the Pale Books.

Mulcahy, Aogán. 1995. “Claims-Making and the Construction of Legitimacy: Press Coverage of the 1981 Northern Irish Hunger Strike.” Social problems 42(4): 449–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3097041.

Northern Ireland Conflict Videos. 2022a. IRA Hunger Striker Bobby Sands’ Funeral, While Unionists Hold a Peaceful Rally to Remember Victims. https://youtu.be/-n9pdnPghuc?t=140 (May 31, 2023).

———. 2022b. “RUC Clashes with Mourners at the Funerals of IRA Members Edward McShaffrey and Patrick Deery, 1987.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SD7SuvCa61g (May 31, 2023).

“Rita O’Hare Obituary: Leading Light in Republican Movement Had a Violent Past.” 2023. Irish times. https://www.irishtimes.com/obituaries/2023/03/11/rita-ohare-obituary-leading-light-in-republican-movement-had-a-violent-past/ (May 31, 2023).

Soldiers Killed at IRA Funeral. 1988b. RTE. https://www.rte.ie/archives/collections/news/21272007-soldiers-killed-at-ira-funeral/ (May 31, 2023).

Sutton, Malcolm. “CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths.” Ulster.ac.uk. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/sutton/tables/Status.html (May 31, 2023).

Sweeney, George. 1993. “Irish Hunger Strikes and the Cult of Self-Sacrifice.” Journal of contemporary history 28(3): 421–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/260640.

The Belfast Agreement. 1998. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1034123/The_Belfast_Agreement_An_Agreement_Reached_at_the_Multi-Party_Talks_on_Northern_Ireland.pdf (May 31, 2023).

The Irish Press. https://www.irishnewsarchive.com/ina_wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Irish-Press-1931-1995-Tuesday-May-05-1981.pdf (May 31, 2023).

Welch, Michael. 2022. “Consecrate and Desecrate.” In The Bastille Effect, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 171–83.