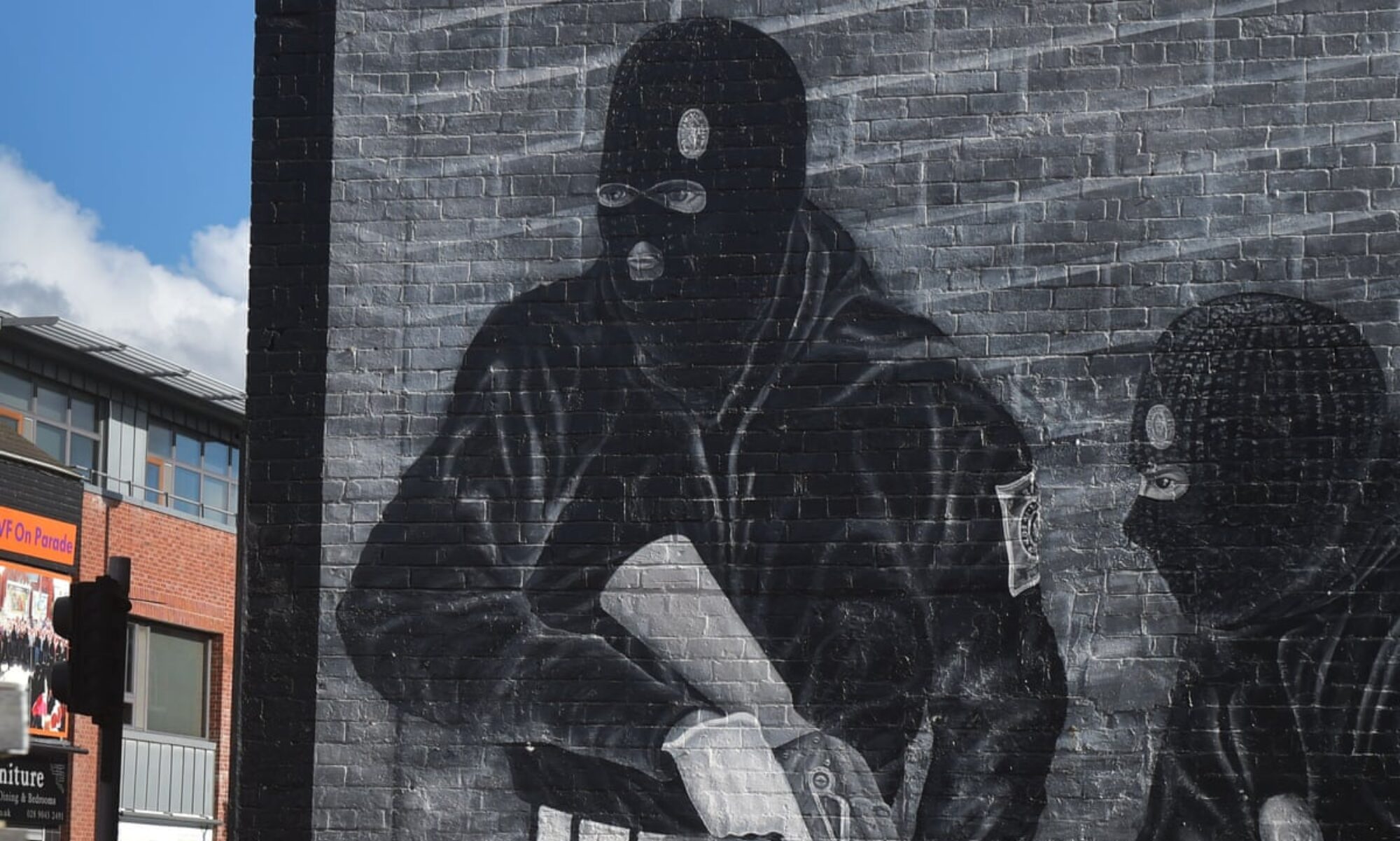

The signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 marked an end to the conflict and a sense of peace for many. However, almost 25 years after the signing of the Agreement, a standing narrative on the conflict remains in large part ‘all my side were heroes, all your side were terrorists.’ The futility of an agreed perspective feels rather prescient when considering the way in which the world learned to view the conflict; the way in which the conflict was documented for the world to see.

In the early 1970s the genre of war photography was budding as a form of international activism. A collective of photographers made their living traveling between the conflict hot spots, such as Vietnam, Guatemala, and, eventually, found Northern Ireland to be the next newsworthy war1. These photojournalists from international media began imposing what had become the broadly accepted representation of violence onto the conflict in Northern Ireland2.

Views from the United Kingdom of Northern Ireland as a politically backwards and socially archaic nation contributed to the simplification of these images to what the world saw3. The coverage of the conflict was largely influenced by the events of Bloody Sunday and the Widgery Reports. The Widgery Reports were set up following Bloody Sunday to understand the civilian deaths on this day and relied largely on photographic evidence4. Despite the creation of many of the photos meant to record the violence of the British, the outcome of the Reports saw more consideration, controversially, given to the British soldiers than to the victims and their families, instead putting the blame on the march organizers1. In the international, and particularly British, perspective of focusing on the acts of violence, the pain felt in those photos for the communities affected has been somewhat divorced from the events themselves as the media focus has been put on the narrative of violence not sadness or loss.

This narrative can be followed into the works created in this period. In comparing the photography and the approach to photographing of British and International photojournalists to that of their Northern Irish counterparts, there is a distinct disconnect between their processes, their images, and their concerns. Patterns of urban conflict and rural idyll dominate many of the internationally recognized photos4 in a design to respect neutrality and objectivity, while Northern photographers are able to capture the violence as it unfolds, allowing the viewer linked to the conflict to decode what is happening given the constructed narrative2.

Exploring the documentation coming out of the nation at this time is that living in and experiencing the trauma produced vastly different visual responses. For these international photojournalists they could fly out to Belfast or Derry for a few days or a few weeks and return to their real lives. For the photographers of Northern Ireland, they went from photographing weddings, awards ceremonies, and sporting events to shooting funerals and soldiers walking down your own streets, many of the perpetrators or victims of the photos being neighbors or friends.

The international perspective on violence in general and specifically towards Northern Ireland created a narrative to be understood throughout the media as one of violence, hatred, and bigotry. In some cases the vision of international photojournalists matched this. The backgrounds and understandings of the conflict played an influential role in the experiences and images created by international photographers and the ones truly living through the Troubles.

Content Warning: Some of the material in the following exhibit may be distressing to some individuals due to the violent nature of select images.

Footnotes

- The Conversation, 2022

- Hutchinson, 2018

- Baker, 2017

- Hanna, 2015