The Orange Order, founded in 1795, has a rich tradition of public marches–called Orange Walks—to celebrate their history and identity. Predominantly held on the Twelfth of July, these marches commemorate the Protestant King William III’s victory over Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, serving as an ever-lasting reminder of the Protestant victory over Catholics.1 The Orange Order’s marches go beyond being mere historical re-enactments. However, imagery of historical figures can be seen on Lambeg drums and banners to commemorate King William III, along with other prominent figures of the monarchy and Protestantism. The marches also serve as assertive displays of Unionist identity and cultural tradition, effectively adapting to changing political circumstances. These parades contribute to the Order’s relevance and longevity despite causing inter-communal tension and often leading to violent conflict. These marches are not simply historical commemorations but robust demonstrations of Protestant and Unionist identity within the ever-evolving socio-political context of Northern Ireland. They effectively illustrate the Order’s continued relevance and resilience over time, despite experiencing periods of inter-communal conflict and tension.2

Even though Orange Order membership has drastically declined since the Troubles, the organization still maintains prominence and is highly engaged in various Northern Ireland Unionist communities. In order to continue to exercise their influence as a group, they assert political beliefs; however, their relationships with different Unionist political parties have shifted over time. Initially, the Orange Order held a long-standing relationship with the UUP; the UUP served as the dominant party that represented the will of the Unionist voters. But, the UUP began to lose favor among the Orange Order, with members seeing the DUP—a more hardline Unionist group—as better suited to uphold Protestant and Unionist ideals. The Good Friday Agreement served as the Order’s transition from the UUP to the DUP, with the DUP opposing the agreement and not being present at the peace talks, showing that concessions to the Nationalists would not be tolerated, which garnered support from the Orange Order. The shifting of the sympathy of the Orange Order from the UUP to the DUP was further entrenched by the DUP and Orange Order both actively supporting a “yes” vote for Brexit. In contrast, the UUP desired to remain a part of the EU. The political transition from the UUP to the DUP was characterized by hardened convictions within the Order and their desire to ensure the continuation of Protestant heritage in Northern Ireland by sympathizing with hardline DUP policies. The Orange Order also established social networks for its members, such as connecting different Lodges, known as Loyalist Orange Lodges, throughout different counties, districts, and even globally.3 These social networks grew and were strengthened by the fact that they are reaching out to younger generations and are embracing more inclusive dialogues.4

The reasons for their attempts to branch out and expand the group are fueled by a deep sense of insecurity towards the growing Nationalist and non-sectarian ideologies in Northern Ireland. The Orange Order views itself as the main bastion of British and Unionist traditional values within a nation that is predominantly Catholic.5 Coming out of The Troubles, the Orange Order fears a loss of their cultural and religious identity in an environment where they are increasingly seen as a minority group. The power-sharing nature of the GFA meant that concessions had to be made on both sides, resulting in members of the Protestant community believing that these changes were diluting their identity. As a result, parades and public displays of Protestant heritage and Unionist traditions/ideals are central to the Orange Order’s mission to preserve the legacy of Unionism and ensure the continuation of Protestantism across the island. These large public festivals organized by the Orange Order each July play a critical role in the organization’s recruitment and upholding/exhibiting their Unionist traditions and Protestant heritage.

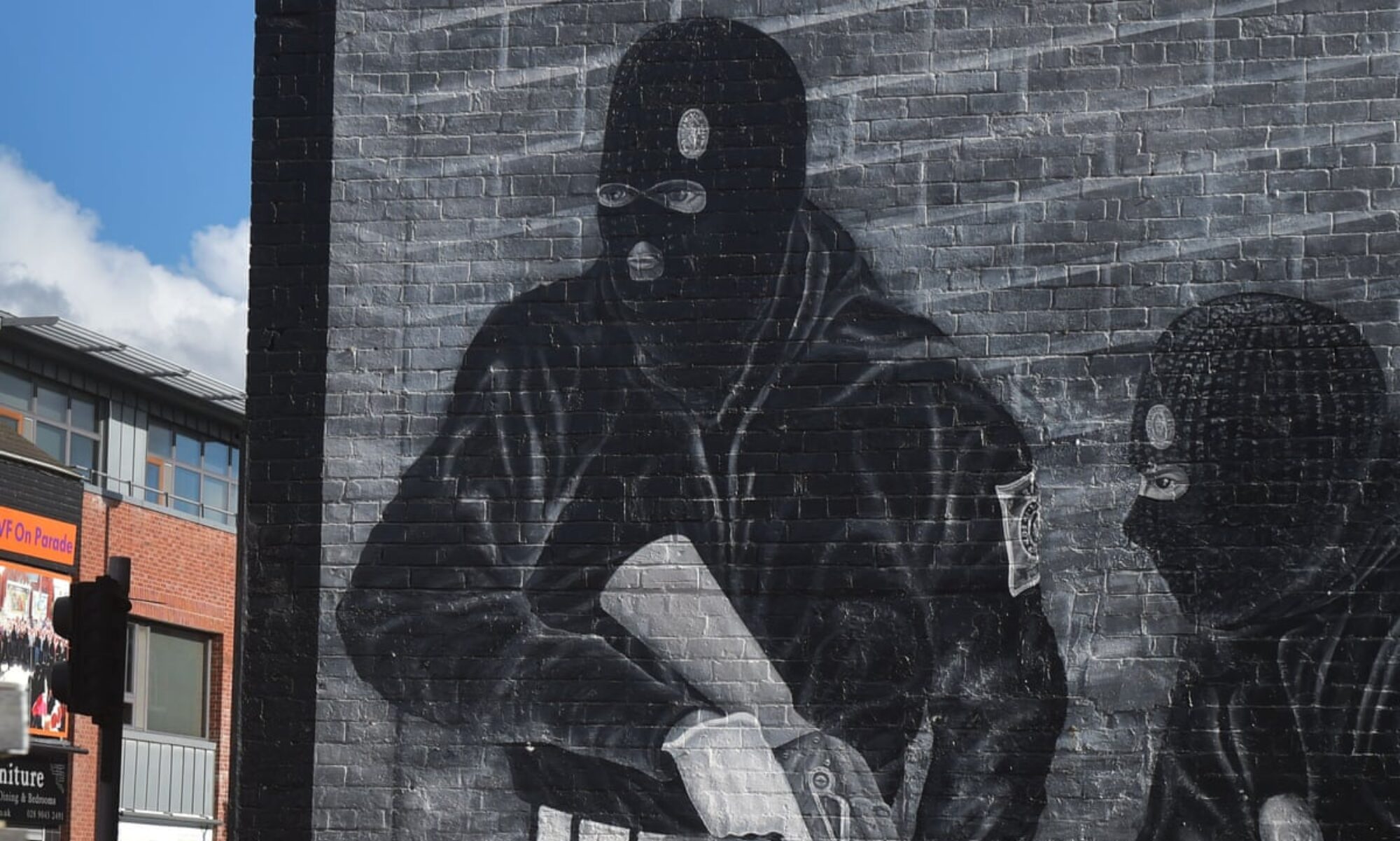

During the marching season, the Orange Walks across Northern Ireland are a constant reminder of the ongoing struggles and the complex legacy of sectarianism in North Ireland. On the one hand, the Orange Order claims they deserve the right to display their cultural traditions; however, these marches often antagonize and lead to bigotry toward Nationalists. The parades and accompanying bonfires often feature disrespectful songs and chants towards Nationalists and, in extreme cases, the burning of effigies, thus inciting fear and violent responses.

An example is the Drumcree conflict in the late 1990s, where members of the Orange Order marched through Portadown’s predominantly Catholic suburb, leading to standoffs and violence. The continued conflict concerning the Drumcree parade led to the passing of the Public Processions Act of 1998, giving the Parade Commission the authority to place restrictions on parades that could potentially lead to public disorder and violence.6 However, unionists and members of the Orange Order criticized the agreement, citing it as yet another infringement upon their cultural traditions. Therefore, public displays of Unionist heritage and traditions, such as the Orange Walks and large bonfires, promote their ideals, help recruit new members, and serve as an intimidation tactic that increases tensions and conflict. The Orange Order marches serve as an example of how cultural expressions in Northern Ireland can, unfortunately, cause adverse effects on relationships between communities.7

Footnotes

- Kaufmann. (2007). The Orange Order : A contemporary Northern Irish history. Oxford University Press.

- Stevenson, C., Condor, S. and Abell, J. (2007), The Minority-Majority Conundrum in Northern Ireland: An Orange Order Perspective. Political Psychology, 28: 105-125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00554.x

- Tonge, Evans, J., Jeffery, R., & McAuley, J. W. (2011). New Order: Political Change and the Protestant Orange Tradition in Northern Ireland. British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 13(3), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2010.00421.x

- Kaufmann. (2007). The Orange Order: A contemporary Northern Irish history. Oxford University Press.

- McAuley, & Tonge, J. (2008). “Faith, Crown and State”: Contemporary Discourses within the Orange Order in Northern Ireland. Peace and Conflict Studies, 15(1), 136–136.

- Evans, J. A., & Tonge, J. (2003). The future of the ‘radical centre’ in Northern Ireland after the Good Friday Agreement. Political studies, 51(1), 26-50. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1467-9248.00411

- Bryan, Dominic. Orange Parades: The Politics of Ritual, Tradition and Control. Pluto Press, 2000. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt18fs351. Accessed 1 June 2023.